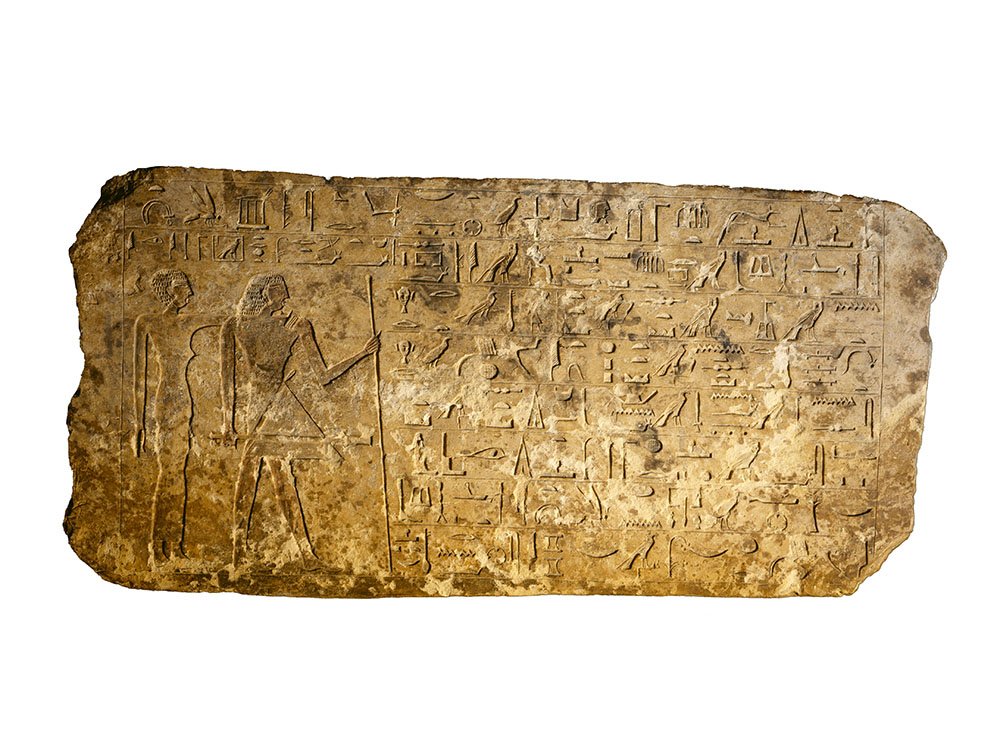

The Stela of hetepneb

by Nikita Owens, University of Manchester

The stela of Hetepneb (1892:224) is displayed at the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin. Its route to the museum is unknown other than it was ‘bought’ (possibly by Dr. Valentine Ball) but it is known that it came from the necropolis of Dra' Abu el-Naga' located on the West Bank of the Nile at Luxor, Egypt.

© National Museum Ireland

Hetepneb, a local administrator, bears the title of “seal bearer of the king, sole companion, lector-priest, overseer of tenants of the palace” and he is shown standing with a stick of authority in his hand and wearing a kilt of the elite. He was, as Margaret Murray (1902) comments, an official of some importance ‘to judge by his own account of himself’! Behind him stands his wife Iri, ‘his beloved, the Royal Acquaintance, the Prophestess of Hathor’. Most of the time women shared the tomb of their husbands and it was just as important for them to have their names, image, and titles carved or painted in the tomb so that their identity was assured in the next life.

Figure 1. Hetepneb’s name Htp-nb

The stela has been dated to the First Intermediate Period of Egyptian history. This period was during the 7th to 11th Dynasties; when the unified rule of the Old Kingdom collapsed, and the country was ruled by separate factions. This stela is a good example of the change in artistic quality during this time when local workshops produced formal monuments with hieroglyphic inscriptions without the controls of rigorous royal or temple sculptural training. Since the elites (those who could actually afford a stela) no longer had access to the high-quality craftsmanship of the court, there was a decline in the standard of the art, though this also allowed some room for innovation. Interestingly, in the left margin outside the framing rectangle, there is a small incised figure of a man, possibly a 'signature' of the sculptor or an addition by a later hand.

Hetepneb’s stela would have been located in his tomb and was used as a focal point of his tomb chapel. The chapel was open to visitors such as family and friends who would continue the provisioning of the deceased by offering food and drink. In contrast, the burial chamber would have been located underground and closed off. The deceased would have gained access to the provisions left by relatives by entering the tomb via a false door: a carved figure of a doorway that was a liminal space between this world and the next.

Stelae such as Hetepneb’s were incredibly important to the tomb owner. They stated the deceased’s name and titles which were essential if the person was to keep their identity and status in the next life. The stela features a reference to the god Anubis; the god of embalming and the necropolis. The tomb owner asks the god, via the king, to provide him with sustenance in the afterlife e.g., bread and beer; staples of the Egyptian diet. On your next visit to the museum call his, and his wife’s name out and offer them sustenance.

The full translation of the stela is as follows:

(1) An offering which the king gives, an offering of Anubis foremost of the divine booth, he who is upon his mountain, he who is in the Embalming Place, lord of the sacred land, so that the king's sealbearer, (2) sole companion, lector-priest, overseer of tenants of the Palace Hetepneb may be buried in his tomb (3) which is in the necropolis in the western desert, having reached a very good old age, on (4) the fair roads of the western desert, upon which the revered ones tread (5) when he has traversed the land and sailed the firmament, may the West (6) extend her arms to him in peace, in peace before the great god. An offering given of the king (to) Osiris (7) lord of Busiris (for) voice-offerings for the king's sealbearer, sole companion, lector-priest (8) the revered one before the lord of Upper Egypt, lord of Qus, whose good name is Hetepneb (9) his wife, his beloved, she who is known to the king, priestess of Hathor, Iri.

Bibliography:

Margaret Murray (1902). National Museum of Science and Art, General Guide III. Egyptian Antiquities, Dublin, 8-9.