Villiers-Stuart’s Egyptian Gleanings

by William Fraher

Henry Windsor Villiers-Stuart was born on 13 September 1827, the son of Henry Villiers-Stuart (1803-1874) of Dromana House, 1st Baron Stuart de Decies and Theresia Pauline Ott of Vienna. In 1850 he was ordained a minister and was appointed vicar of Bulkington, Warwickshire in 1852. He paid his first visit to Egypt in 1849 and again in 1858/59 with the intention of visiting sites mentioned in the bible.

On 3 August 1865, Henry married Mary, daughter of Venerable Ambrose Power, archdeacon of Lismore. In 1873 he resigned Holy Orders in order to run for parliament as M.P. for Co Waterford and by July had won the county Waterford by-election, standing in the liberal interest. On the death of his father in 1874 he succeeded to the Dromana estate. He did not succeed to his father’s title as no record of his parent’s marriage could be found. He brought the case before a committee of privileges in 1876 but was unable to prove his right to succeed as 2nd Baron Stuart de Decies.

In December 1878 Villiers-Stuart and his wife set off on his exploration of the Nile in and returned in March 1879 after which a detailed description of his trip and the monuments he visited was published in 1879. He states that the cost of a winter in Egypt based in Cairo cost sixteen shillings a day per person! A boat trip on the Nile by dahabeeah cost five pounds per day for a group of three. He commented that the trip was worthwhile even for those without a great interest in history: ’The restorative effects of expeditions on camel-back, donkey-back, or on foot, to visit monuments which must excite something like enthusiasm even in the most matter-of-fact minds, no medicines which no apothecary’s shop can supply’.

He and his wife Mary left from Marseilles on the Iraouaddy, the largest steamer in the Messageries Maritimes. The ship docked at Port Said for coal and the passengers disembarked for a stroll. ‘We sat at little tables and sipped curacao punch…We saw some queer-looking people about, and accidents with stilettos are not uncommon.’

The passengers stayed for a few days at the Netherlands Hotel before continuing their journey up the canal to Suez. The following day they hired a dhow and brought a donkey on board, and sailed down the east coast of the Red Sea. From Suez they travelled by train to Cairo. There they hired a boat from Messrs Cook & Co. It was an iron dahabeeah called ‘The Gazelle.’ Along the river they encountered local people and guides who took them on visits to sites of archaeological interest. While Villiers-Stuart was interested in seeing the known sites of significance he was always in search of new places and probably hoped to discover something of significance. However, most guides did not like to deviate from the standard tourist trail.

The Villiers-Stuarts visited the Crocodile Caverns of Gebel Aboufaida on 17 December 1878. He was accompanied by four guides and an interpreter. His description of exploring this cave is worth quoting as it conveys the sense of danger, mystery and terror involved:

We started from Shalagheel for the crocodile mummy caverns. After an hours ride across the desert we came to an insignificant looking cleft in the surface – this was the entrance to the cavern. The four guides were furnished with candles, and Elias then addressing me, cooly proposed that I should go down with them alone, and he would await my return. I insisted on his accompanying me, as otherwise I had no means of making myself understood…With a heavy sigh he ‘caved in’ and agreed to go.

The men now stripped stark naked, and each entered with a candle and a dagger…After we had proceeded for about 50 yards I heard Elias exclaiming in a very lamentable tone: ‘I cannot, I cannot do it; please let me stay…so I decided to go on without him. We noticed that the rocks were covered with a sticky, greasy, black deposit, like tar. Our guides informed us that this had been caused by a fire….

The atmosphere grew worse and worse as we proceeded; the heat was suffocating, and there was an overpowering smell of ammonia. Sometimes the passage was so low and narrow that it was with difficulty we crawled through…our lights were repeatedly extinguished by the bats which flew in our faces incessantly, almost blinding us. I would have given anything for a tumble-full of brandy...at last we emerged into a chamber that was 15 feet across…the floor was covered with palm branches, placed there… for the mummies to repose upon…All about lay mummies of crocodiles and men. Igniting some magnesium wire, the brilliant light fell upon such a scene as Dante never dreamt of for his Inferno. The naked bronze figures of my guides with their daggers, the strange weird forms of the reptiles, with their long snouts displaying rows of sharp white fangs, the grinning human heads, thick curly hair, and white gleaming teeth and hollow eyes, that seemed to reproach us for disturbing their rest. All this informed an experience never to be forgotten, and scarcely to be surpassed by the wildest nightmare.

Suddenly one of the men gave a cry of horror and snatched the magnesium wire out of my hand, for a spark of it had fallen amongst the palm branches, and had they taken fire, we had never more emerged alive. We once more dived into a narrow passage…the air grew even worse, and I could scarcely breathe…the men…tried to encourage me with the words: ‘more mummies’, but I felt that if I stayed much longer I should join the ghostly company myself… I shall never forget the delirious sensation of the first taste of fresh air…I felt as if I had just awoke from some grim nightmare.

He asked the guides why the mummies were in such disarray. They replied that the Viceroy had removed many of the mummies and that a German speculator had paid locals to gather as many as possible to turn them into superphosphate.

Henry Windsor Villiers-Stuart was a member of the Egypt Exploration Fund. He was concerned about the damage to Egyptian monuments and like Amelia Edwards, one of the founding members of the EEF, he noted how quickly sites were being destroyed. In his book Egypt After the War (1883) he noted with alarm the damage done to sites he had visited in 1879:

The process of destruction is going on so rapidly at Deir-el-Bahari, that I have thought it well to publish further drawings of its bas-reliefs before they disappear for ever. Some of the subjects which appeared in ‘Nile Gleanings’ have already been stolen or destroyed – that is the case with the tableau of the archers of Queen Ha-te-Sou. I learned that the stones had been carried away in a dahabeeah by some travellers, and I observed that a considerable portion of the wall had been pulled down and destroyed to get at it – the whole temple had been terribly wrecked since my last visit in 1879.

He also noted that some of the tombs in the Western Valley in Thebes had been badly damaged. He made notes and drawings of what remained, in particular at the tomb of Aii, at Tel-el-Amarna.

In Nile Gleanings he commented that:

When I was in Egypt before, anyone might, without let or hinderence, plunder these tombs and hunt for mummies, the consequence was that the ancient cemeteries were littered all over with fragments of mummies. They were dug up by the hundreds and torn to pieces in search of jewellery and antiquities. This robbery of tombs is now strictly prohibited under severe penalties.

Publications on Egypt

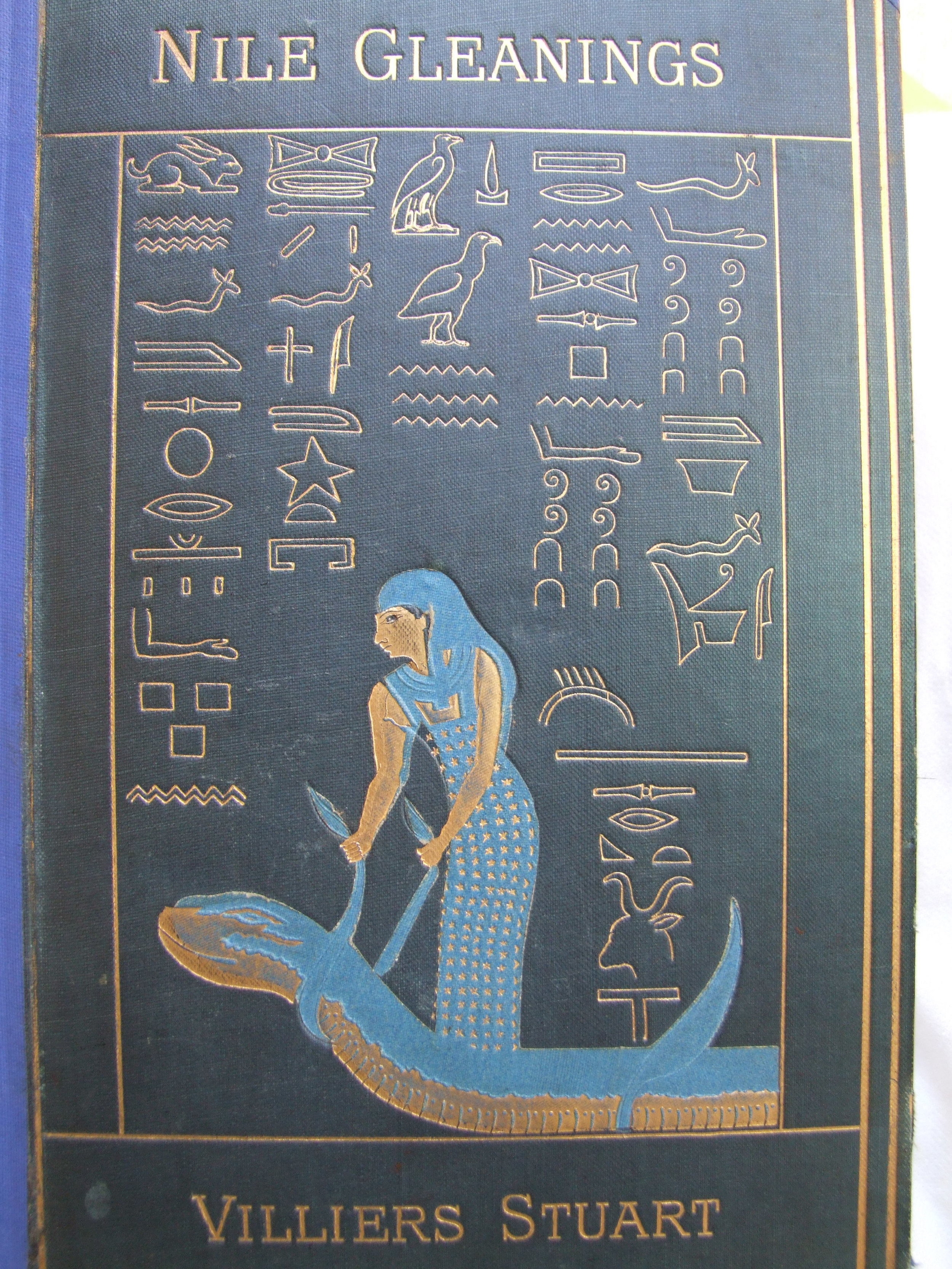

In 1879 Villiers-Stuart published Nile Gleanings – concerning The Ethnology, History and Art of Ancient Egypt As Revealed by Egyptian Paintings And Bas-Reliefs - With Descriptions of Nubia and its Great Rock Temples to the Second Cataract.

This substantial work contained 58 coloured and outline plates ‘from sketches and impressions taken from the monuments’.

The author is clear as to his style of writing and his intended audience: ‘My object has been to give a popular account and a general idea of the elements of Egyptology to those who have not leisure, patience or inclination to go deeper. I have adopted a light sketchy style hoping to render the subject acceptable to the general reader.’

In the preface he makes the point that even though many books had been written on Egypt: ‘much still remains to be discovered there; much of what has already been discovered still remains to be described.’ He says that he avoided describing things which have already been published and refers to his discovery of a new tomb.

The book is illustrated with his own drawings all signed with the initials HVS and dated 1879:

The illustrations, with few exceptions, are from my own drawings. Some were sketched from the monuments…in some I have been assisted by impressions taken by myself from the bas-reliefs; in others I have been aided by photographs. Many of the plates must be understood to be restorations, but no colour or pattern has been introduced without the authority of the monuments. In most cases amply sufficient colour remained to guide me…Indian red and vermilion, Naples yellow and chrome, olive green, indigo blue, light blue, and lamp black were the stereotyped pigments.

It is worth noting that Henry was in contact with some of the most important Egyptologists of the period before submitting his manuscript for publication. It shows the attention to detail and the accuracy with which he approached his research. It is not known how Mariette, Brugsch and Birch viewed his findings.

The Funeral Tent of an Egyptian Queen

In 1882 Villiers-Stuart published the following work:

The Funeral Tent of an Egyptian Queen. Printed in colours, in facsimile, from the author’s drawings taken at Boulak. Together with the latest information regarding other monuments and discoveries. With translations of the hieroglyphic texts and explanatory notices of the various emblems. London: John Murray, 1882.

This book, like his other publications was produced to a high standard with black and white and colour plates. It contains a large colour lithograph of the funeral tent which is signed: ‘Villiers Stuart, Cairo 1882.’ The tent belonged to Isemkhebe B and was discovered at Thebes in 1881. Gaston Maspero, Director General of excavations and antiquities in Egypt, allowed him to examine it and make drawings:

The tent itself may be described as a mosaic of leather work, consisting of thousands of pieces of gazelle hide…The colours consist of bright pink, deep golden yellow, pale primrose, bluish green and pale blue.

In 1882 Henry attended a meeting of the Biblical Archaeological Society and showed his drawing of the tent:

Mr. H. Villiers-Stuart, M.P., in exhibiting a large coloured drawing of the remarkable funeral canopy lately discovered near Thebes, produced some fragments of the original leather, the colours of which were now as the day they were made. He further, as illustrations of the paper by Mr. Lund, exhibited paper squeezes of the heads of Amenhotep IV and Khuenaten, from the figures which respectively occur on the opposite sides of the façade of the tomb, which he himself had discovered and excavated at Thebes.

The ‘tent’ was found in what is known as ‘The Theban Tomb’ 320 at Deir-el-Bahari by Emile Brugsch in 1881.

The book was reviewed in a number of newspapers and periodicals. The Times of 5 July 1882 noted that Villiers-Stuart’s colour image was the first to reveal the true beauty of the object. The Morning Post (26 Aug 1882) described the book as ‘one of the most interesting and valuable contributions to Egyptian lore that has appeared this year’.

The baldachin is the largest piece of leather-work to survive from ancient Egypt and is now considered an object of world heritage value. In 2012 a project to restore the canopy was instigated by the Russian Academy but it was stalled due to the political situation. It would be wonderful to see this amazing survival, fully restored in the new Cairo museum.

After the Battle of Tel el Kebir the British government appointed Henry Windsor Villiers-Stuart to accompany Lord Dufferin’s delegation to visit Egypt and report on the condition of the people. His reports were published in a series of blue books which were praised for their thoroughness and insights.

In 1882 Thomas Birch of the British Museum wrote to Villiers-Stuart about the proposed destruction of the Cairo Museum (VSP BL/EP/VS/153(2):

Like myself you are no doubt pleased at the successful issue of the Egyptian campaign and the country will now it is hoped return to comparative tranquillity. The Museum of Boulak fortunately escaped as Maspero wrote to me that some of the ‘patriotic’ party in case of defeat intended destroying the museum, the theatre and the tombs of the Mamelouts, ‘toys’ of the Europeans and Christians. We took all precautions possible here and lieutenant Chermside instructed to look after the museum and Sir Garnet Wolsley written to by the War Office about it. Maspero…has not yet answered my letter inquiring about the fate of the gold objects. There was a report some things had gone to Paris.

Egypt After the War

Villiers-Stuart published Egypt After the War in 1883 to expand on the content of his government blue book reports on Egypt. In his introduction he states that he hoped it would help to ‘emancipate the oppressed classes in Egypt…

My sympathies are with the mass of the people of Egypt. I have faith in their capabilities, if only a fair chance be given to them; they are industrious and intelligent. The fact that they still retain any good qualities, notwithstanding the cruel mis-government and oppression to which they have for centuries been subjected, speaks volumes in their favour’ (1883, vii).

The book contains much useful detail on the social history of Egypt but a large portion is devoted to the antiquities of the country. The book was well received by the public and reviewers, some of whom felt that the mixture of contemporary and ancient history was a more enjoyable read. Amelia Edwards gave a favourable review: ‘Of the wrongs and sufferings of that unhappy peasant Mr Villiers Stuart draws a heartrending picture. [He has] an acquaintance with Egypt which extends over a period of nearly thirty years’.

During the winter of 1882 he discovered the alabaster altar and basins in Niuserre’s Sun Temple at Abu Ghurab. He states that he applied to Emile Brugsch for permission to excavate the site further. Amelia Edwards singled out this discovery as significant; ‘Mr Villiers Stuart’s discovery of the remains of a funerary chapel built apparently of alabaster, in enormous blocks…and the simultaneous discovery of ten large alabaster basins, each measuring fifteen feet in circumference…are facts of real interest and value.’

Tomb of Ramose TT55 also known as ‘Stuart’s Tomb’

On 8 February 1879 he visited Khou-en-Aten and claimed to have discovered a tomb of a governor of Thebes which he wrote about in Nile Gleanings: ‘I was fortunate enough while at Thebes to discover a tomb which had hitherto escaped notice, having been completely buried beneath quarry rubbish. On the left-hand side of the entrance was a bas-relief of Amunoph IV, and on the right was another of Khou-en-Aten’.

The tomb was built by Ramose, a Vizier and Governor of Thebes in the 18th Dynasty. It was situated in the hills at Shekh Abd-el-Kurnu on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor. Whatever about his claim to have discovered the tomb there is no doubt that Villiers-Stuart’s report on the site and the publication of his drawings brought the monument to the attention of a wider public. Villiers-Stuart did further work at the tomb in 1882. Gaston Maspero continued excavating after Stuart. The tomb was restored in 1924 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

this Mr Villiers Stuart came in and began to talk of mummies and the covering of the sacred ark. Visited Beulah museum with Mr V. Stuart.

Villiers Stuart’s Egyptian Collection

Villiers-Stuart had amassed a collection of Egyptian artefacts during his visits to Egypt which were stored in his home at Dromana. The Egyptian collection at Dromana was given on loan to the National Museum of Ireland in 1921 by Ion Villiers-Stuart (Loan 1129:1-246). It is interesting to note that Harriet Kavanagh’s collection of Egyptian artefacts had been transferred to the museum the previous year from the Royal Society of Antiquaries. In 1969 the artefacts were removed by the Villiers-Stuart family and they were sent for auction to Christies in London. The collection was sold on 14 April 1970, as lots 55 to 84 in their sale of ‘Important Egyptian Antiquities of the Predynastic, Dynastic, Classical and Coptic Periods.’

Two of the artefacts are illustrated in the catalogue, lots 80 and 82. Lot 80 was a painted wood funerary stele (31.0cm high) dating from the 31st Dynasty. Lot 82 (Sold Christies 1 October 2014 as Lot 170) is a fragment of a painted limestone stele (27cm high) from the tomb of Penbuy, a craftsman working in the Valley of the Kings at Deir-el-Medina.

Fortunately the National Museum of Ireland’s list of the collection survives in the archives and records 246 objects. Three artefacts from the collection remain in Ireland, a painted cartonage and two small wooden figures with traces of paint and plaster.

A printed A3 catalogue listing the items he loaned survives titled: Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities collected by Mr. Villiers Stuart of Dromana, in 1877-8, 1879, and contributed to the Waterford Exhibition.

Villiers Stuart was drowned on 12 October 1895. He was getting off his launch when he slipped and fell into the river and drowned. He was aged 68.