Richard Pococke

Richard Pococke’s Travels in Egypt 1737-39

Born in England in 1704, with clergymen on both sides of his family, the early Egyptologist Richard Pococke began his church career in Waterford at the gift of his uncle, Thomas Milles, Bishop of Waterford & Lismore. His first preferment was as Precentor (or Chantor) of Lismore Cathedral (1725), after which he received several other appointments, but it was not until 1745, on his promotion as Private Chaplain to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, that he actually took up residence in the country.

Aged twenty-nine, and therefore considerably older than the norm, Pococke embarked on his first Grand Tour in 1733 with his younger cousin, Jeremiah Milles, and together they visited the usual cultural centres of France and Italy, culminating in a substantial sojourn in Rome. Recalled after only nine months, in order to allow Jeremiah Milles to take up an appointment as Precentor of Waterford Cathedral (1735), the cousins spent the next two years planning a more unusual second Grand Tour which would eventually take Pococke to Egypt and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. They set out in the summer of 1736 and travelled around central Europe, visiting the lesser-known countries of the Habsburg Empire, but their travels were interrupted for a second time, in the autumn of 1737, when Jeremiah Milles was persuaded to return to Waterford to tend to the bishop, who was suffering from gallstones - a condition from which he eventually died. The cousins parted company in Trento and Pococke, having obtained in Venice a Firman or Ottoman passport, embarked on a ship to Alexandria in what was to be one of the most intrepid voyages of the period.

Though he travelled throughout the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean, spending four years in Egypt, the Holy Land, Lebanon, Syria, the Greek Islands, Turkey and mainland Greece, he is best known for the scholarly and detailed observations he made on Egypt. With a tactical dedication to Henry Herbert, 9th Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery (the so-called “architect earl”), [Figure 1] these observations were presented in Volume 1 of his lavishly illustrated book, A Description of the East & some other Countries (1743). Though condemned by two rival writers of eastern travels - Dr Charles Perry (1743) and Rev. Thomas Shaw (1746) - Pococke’s publication was an immediate success and was followed by a second volume (1745) which described all the other places he had visited in the east.

Figure 1. Illustration from Dedicatory Page, Pococke (1743)

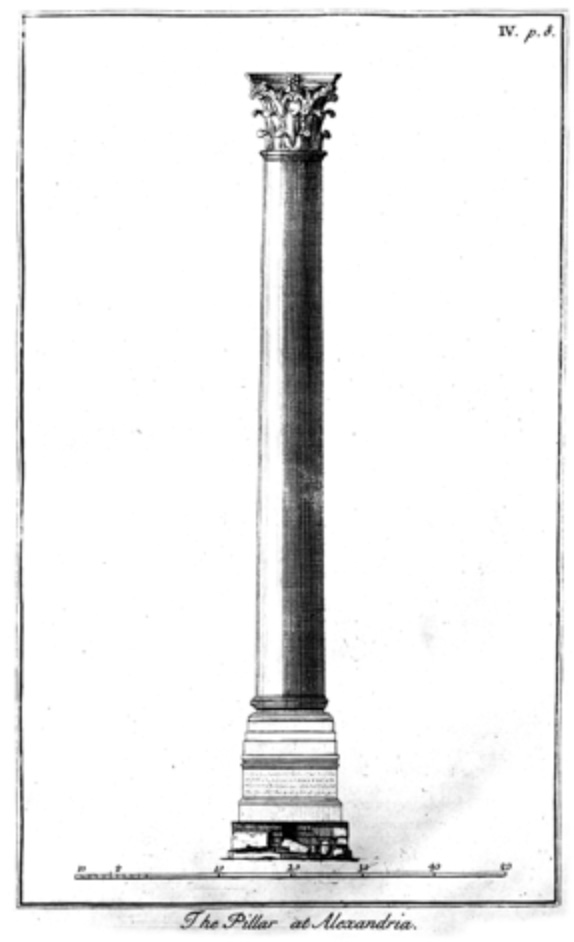

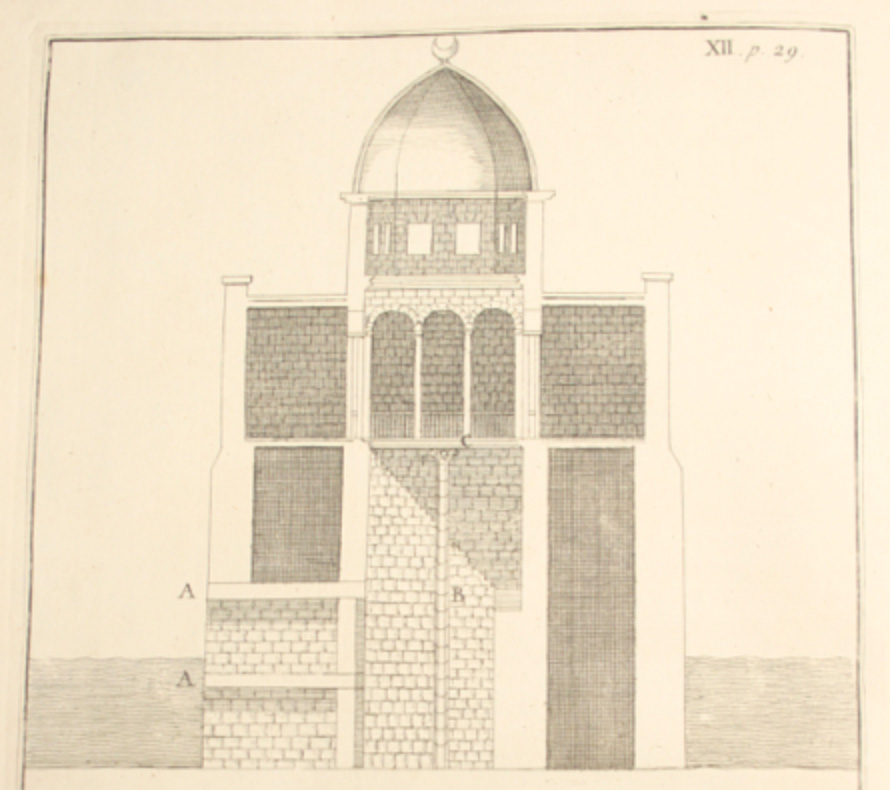

During his far-reaching and intrepid eastern voyage, Pococke made two separate tours of Egypt. The first was in early September, 1737, when he set sail from Livorno to Alexandria. After a three-week stay in the capital, where he greatly admired “Pompey’s Pillar” (Figure 2), he visited Rosetta, later embarking on a galley to travel up the Nile to Grand Cairo. After almost a month in that city, where he was intrigued, among other things, by the “Mikias”, a device for measuring the height of the Nile (Figure 3), he took a boat to Akhmim, where he spent Christmas in a nearby convent. He then visited Karnak and Luxor, where he viewed the famous antiquities for a period of four days, and then continued to Aswan, which he reached in late January, 1738. From there he proceeded to Adfou, Etne and El Qurna, where he visited the famous tombs of the kings, (Figure 4) and on his return journey to Akhmim visited Quena, Dardana and Girga. He arrived back in Cairo at the end of February, after an absence of twelve weeks with virtually no English company; and in a letter to his mother, noted that “it was like coming home”. (R. Finnegan, 2013, p.25)

Figure 2. The Pillar at Alexandria, Pococke (1743), Plate IV and Figure 3. A Plan of the Mikias at Cairo to measure the height of the Nile, Pococke (1743), Plate XII;

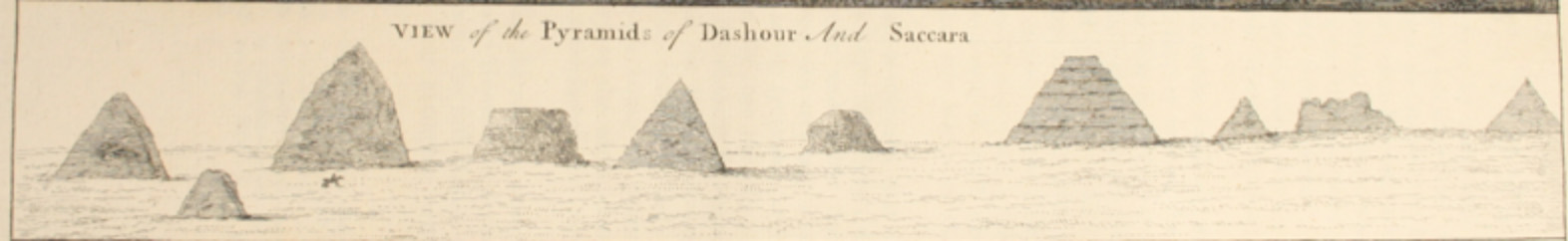

Figure 4. The Sepulchres of the Kings of Thebes, Pococke (1743), Plate XXX; Figure 5.View of the Pyramids of Dashour and Saccara, Details from Pococke (1743), Plate VIII.

In March, Pococke sailed from the port of Damietta to Jaffa on a pilgrim boat, and after a ten-month voyage of the Holy Land, Lebanon, Syria and Cyprus, arrived back at that port on Christmas Eve, 1738. Two days later he sailed to Cairo, where he remained for three months, during which time he visited the pyramids at Giza and at Saqqara (Figure 5). At the end of March set out for Mount Sinai with the caravan, where he stayed over the Easter period, and in late April revisited Cairo, Rosetta, and Alexandria. On 2 July, he embarked on a ship to Crete, thus ending his tour of Egypt.

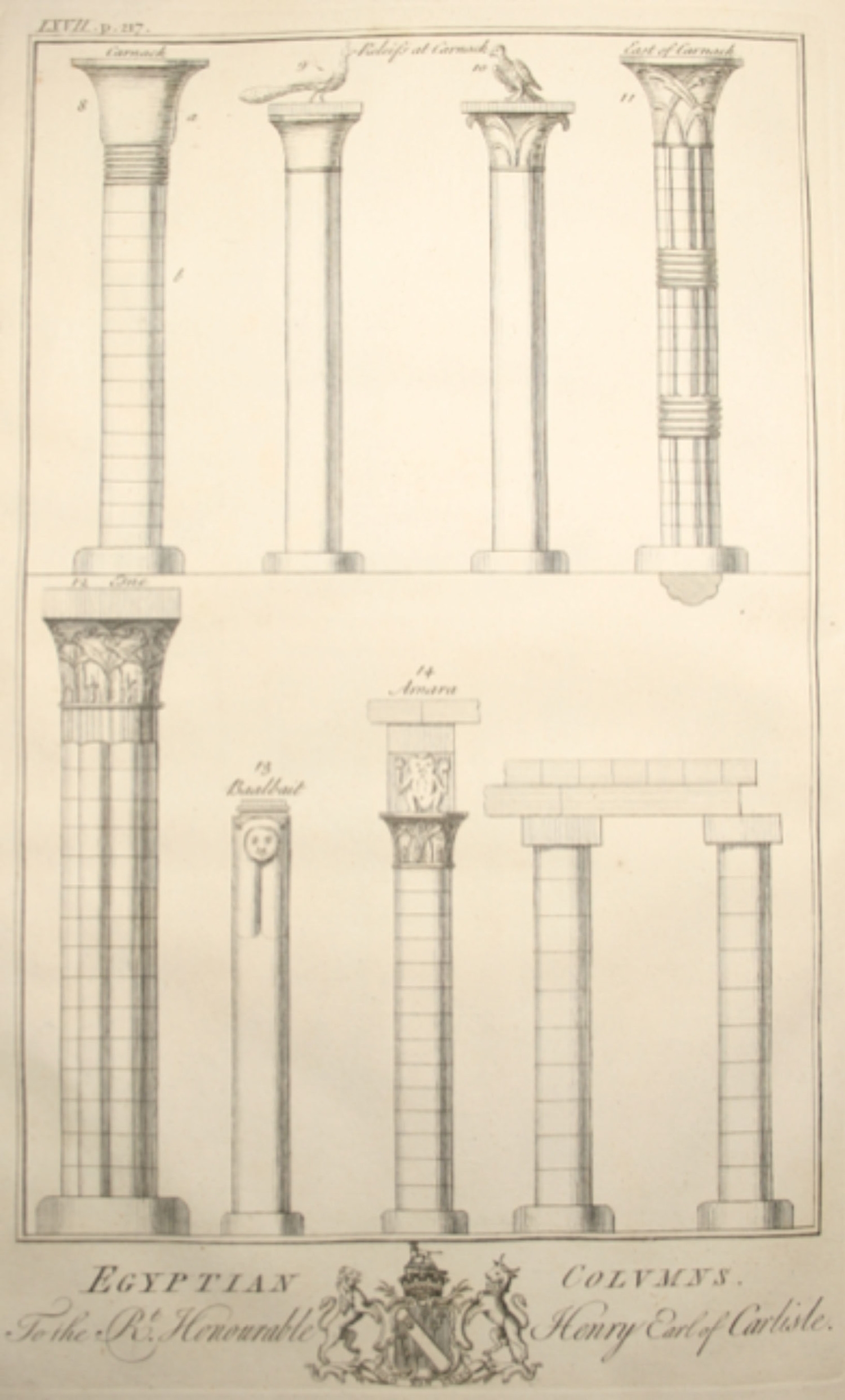

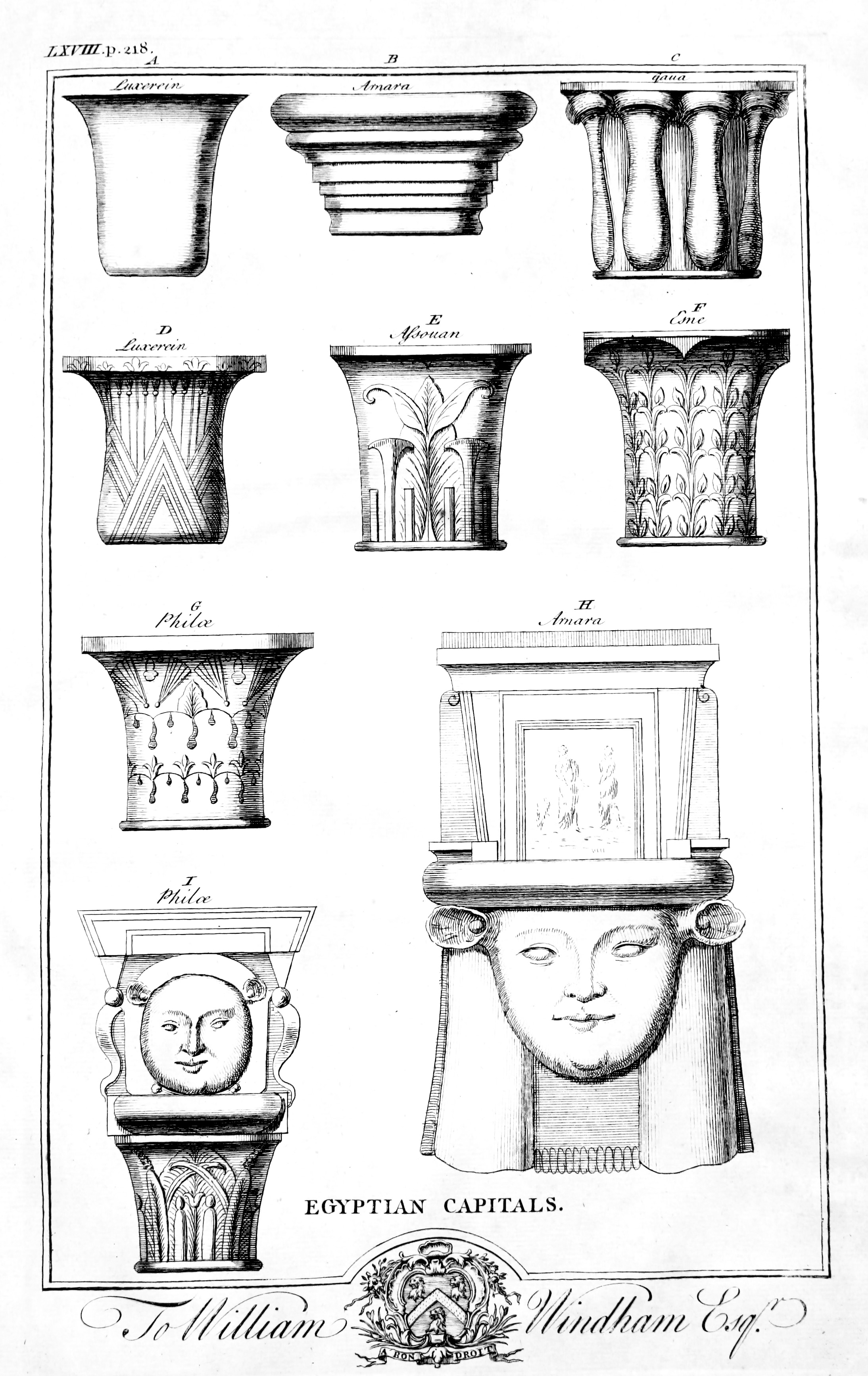

As one of the more scholarly grand tourists of his day, Pococke devoted a great deal of time and attention to his study of all aspects of Egyptian culture. The resultant book (1743) is famous not only for its abundance of architectural drawings (five of which are devoted to the different types and parts of columns) (Figures 6 and 7) but also for its explanations of ancient and more recent history. He also gave vivid descriptions of contemporary life in Egypt; and it is this aspect of his work that earned him the reputation as a pioneer in anthropology. He was a serious collector, too, and while travelling in Egypt accumulated an interesting assortment of coins, medals, antiquities (including two human mummies and a pair of block statues) and natural curiosities. These were shipped back to his mother in England for his cabinet of curiosity and as far as we know, they were kept together for his life-time, only being dispersed by auction following his death (see R. Finnegan, 2014, forthcoming).

Figure 6. Egyptian Capitals, Pococke (1743), Plate LXVIII Figure 7. Egyptian Columns, Plate LXVII

As for the more social aspects of his Egyptian experience, Pococke spent much time in the main cities (Alexandria, Rosetta and Cairo) receiving and returning the hospitality of the “Franks” or foreign residents, particularly the English, French and Dutch consuls, and the merchants associated with the English trading houses. The textile trade to which these individuals belonged had an added appeal for Pococke: as is evident from his portrait in exotic eastern costume (Figure 8); the letters to his mother with their frequent descriptions of clothes and draperies; and his establishment in later life of linen weaving works in Ireland, he had more than a passing interest in fabrics and their manufacture.

Figure 8. Portrait of Richard Pococke by Jean-Etiènne Liotard (1740), oil on canvas, Courtesy of the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire do la Ville de Genève

There are three sources for Pococke’s travels in Egypt: the above mentioned volume of his travels (1743); an unpublished Note Book describing his voyage from Livorno to Alexandria (British Library, Add. 22995); and two extensive collections of manuscript letters. The first collection (recently edited and published by R. Finnegan, 2013) comprises letters sent by Pococke every two to three weeks to his scholarly mother Elizabeth Pococke, whom he addressed as “Honoured Madam” (British Library, Add. 22998). In return for keeping her appraised of his movements and continually reassuring her of their promised reunion in the family home, Newtown House (Figure 9), Mrs Pococke managed her son’s affairs, dealt with his correspondence and took charge of the antiquities and natural curiosities that he sent back to England. These letters are light, informative, personal and witty. By contrast, the second collection was sent in irregular batches to his uncle and patron Bishop Milles and comprises formal “Accounts” of his observations on Egypt (British Library, Add. 15779). These accounts, which are largely devoid of personal content and written in a more studied and academic style, are addressed to “My Lord”. This collection has not yet been published , but the present author intends to edit and post them up on her website over the coming months, together with the edited transcripts of five Egyptian letters from Pococke to his mother (four sent from Grand Cairo and one from Alexandria) for the period January to July, 1739. The latter were summarized rather than transcribed in her recent edition (2013, pp 193-97 and pp 207-8).

Figure 9. Early Photograph (pre 1863) of the Pococke family home in Newtown, near Newbury, Berkshire/Hampshire, private collection

Pococke’s contribution to Egyptian scholarship in the west is immeasurable, and though in later life he turned his attention to different antiquarian pursuits (Herity, 1969 and Ireland, 2008), he has retained his reputation as an early Egyptologist. For a man so illustrious in his life-time, and whose scholarly works have continued to command respect world-wide, it is sad that he ended his days alone (he never married) and in humiliating circumstances, with the publication of a scathing satirical poem (1765) that sought to destroy his personal, professional and academic name. This is compounded by the fact that his plain and ill-spelled epitaph (“here lies intered the body of docter Richard Pococke of Meath who died September 15th 1765 in the 63rd year of his age”) on the monument in Ardbraccan churchyard in Meath, makes no reference to his legendary work on Egypt.

Figure 10. Frontispiece to Pococke (1743)

Bibliography

[Anon.] Meekness or Ambition: the Hypocrite Detected. In a Dialogue between R—h—d, an I-r-h B-sh-p, and S-s-n, a favourite Ch-b-m-d. On Occasion of his L—s—p’s being resolutely oppos’d and ignominiously defeated in an Encroachment he had long meditated and lately attempted upon the Perogative of a certain D—n, and the Rights and Privileges of his Ch—t-r (London, no date: probably false imprint and should be Dublin, 1765).

Finnegan, Rachel, www.pocockepress.com.

Finnegan, Rachel (2014, forthcoming), “The Travels and ‘Curious’ Collections of Richard Pococke, Bishop of Meath”, in Journal of the History of Collections, Oxford.

Finnegan, Rachel (2013), The Grand Tour Correspondence of Richard Pococke & Jeremiah Milles, Volume 3: Letters from the East, 1737-41, Pococke Press, Ireland.

Herity, Michael (1969), “Early finds of Irish antiquities: from the Minute-Books of the Society of Antiquaries of London”, in Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 49, pp 1-21.

Ireland, Aideen (2008), “Richard Pococke (1704-65), Antiquarian”, in Peritia, Volume 20, pp 353-78.

Perry, Charles (1743), A View of the Levant: particularly of Syria, Egypt, and Greece. In which their Antiquities, Government, Politics, Maxims, Manners, and Customs, (with many other Circumstances and Contingencies) are attempted to be Described and Treated on), London.

Pococke, Richard (1743), A Description of the East and of some other Countries, Vol. I, Observations on Egypt, London.

Pococke, Richard (17450), A Description of the East and of some other Countries, Volume II Part I: Observations on Palaestina or the Holy Land, Syria, Mesopotamia, Cyprus and Candia; Volume II. Part II: Observations on the islands of the Archipelago, Asia Minor, Thrace, Greece, and some otherParts of Europe, London.

Pococke, Richard, “A Voyage from Leghorn to [Alexandria]” (British Library, Add. 22995).

Pococke, Richard, Letters to Mrs Elizabeth Pococke, copies (British Library, Add. 22997).

Pococke, Richard, Register of Letters from R. Pococke to Bishop of Waterford (British Library, Add. 15779.

Shaw, Thomas (1746), A Supplement to a book entituled Travels, or Observations, &c. wherein some Objections, lately made against it, are fully considered and answered: with several additional Remarks and Dissertations, Oxford.